On November 11 there is a transit of Mercury, when, as viewed from Earth, Mercury passes across the face of the Sun. (Almost needless to say, but never view the Sun directly, either with the naked eye or with any form of optical instrument. Always use a proper solar filter – the ones that look like aluminium film – a solar telescope, or project an image onto a card for safe viewing.)

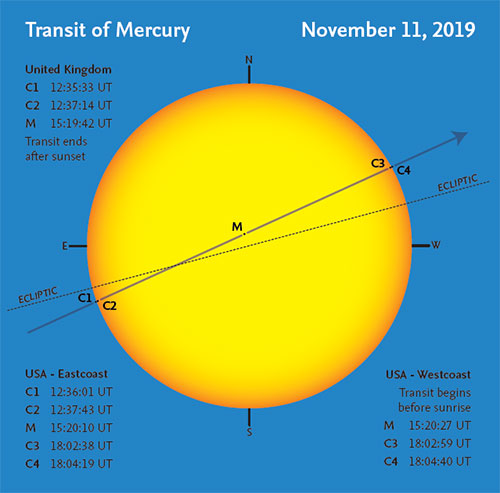

Because of the rotation of the Earth and the motion of the planets, transits are not visible from every part of the Earth. With the transit on November 11, the beginning and middle of the transit are visible from Great Britain, but the end is invisible after sunset. In the United States, the beginning, middle and end are all visible from the East Coast, but on the West Coast, just the middle and end are visible.

Transits are rare. They may occur only with the inferior planets, Venus and Mercury, that are inside the Earth’s orbit. Transits of Mercury do not occur every year, and even then come only in May or November, when the locations and orbits of Mercury and Earth are suitably aligned. (An interval of 13 years between transits is the most common timing.) Following the transit on November 11, 2019, the next transit will be on November 13, 2032.

Transits of Venus are even rarer. They occur in pairs, separated by eight years, and in a pattern that repeats only every 121.5 years and 105.5 years. The last pair were on 8 June 2004 and 5—6 June 2012. The next pair will not occur until 10—11 December 2117 and 8 December 2125.

Transits, particularly of Venus, were very important historically, because they could be used to determine the sizes and distances of objects in the Solar System (not just Mercury, Venus and the Sun). Some important expeditions to various parts of the world to observe transits were carried out in the 17th and 18th centuries. Nowadays, the transit method is the main way in which the existence of exoplanets (planets orbiting stars other than our Sun) is determined.

By Storm Dunlop with charts by Wil Tirion, authors of Guide to the Night Sky 2020

Storm Dunlop is an author and translator, working in the fields of astronomy and meteorology. He is a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, the Royal Meteorological Society and a member of the International Astronomical Union.

Wil Tirion was trained in graphic arts and has always had an interest in astronomy and especially star charts. He has contributed to many atlases, books and magazines. In 1993 a minor planet was named after him: (4648) Tirion = 1931 UE.

collins_dictionary_official

The home of living language. #wotd #wordlovers #collinsdictionary

Read our word of the week definitions and blog posts: