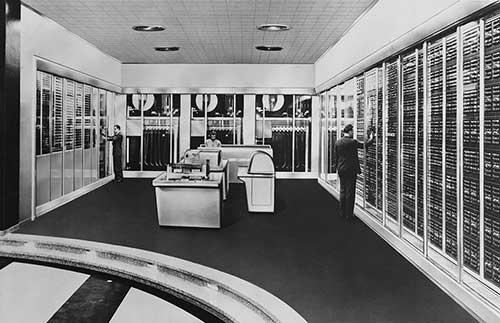

By the time I arrived at COBUILD as part of the 1993 intake recruited to work on the second edition of the dictionary, the whole project had been fully computerised for several years. This meant working on screen at terminals linked to mainframe computers that hummed away in a separate room, still with the green text on a black background, as described by Andrew Delahunty in Part 1. The mainframe computers were named after Shakespeare characters –Titania was one – and would occasionally overheat and need time to recover, giving us the afternoon off.

A mainframe computer, similar to those used at the University of Birmingham in the 1990s

There was a pleasing contrast between the high-tech, cutting-edge nature of the project and the elegant Victorian building where we worked, with its large sash windows overlooking a beautiful garden where we would sometimes eat our lunch in the summer. It was also a great place for seminars and parties, both of which would bring in members of the English department of the University of Birmingham to which COBUILD was attached and the wider university.

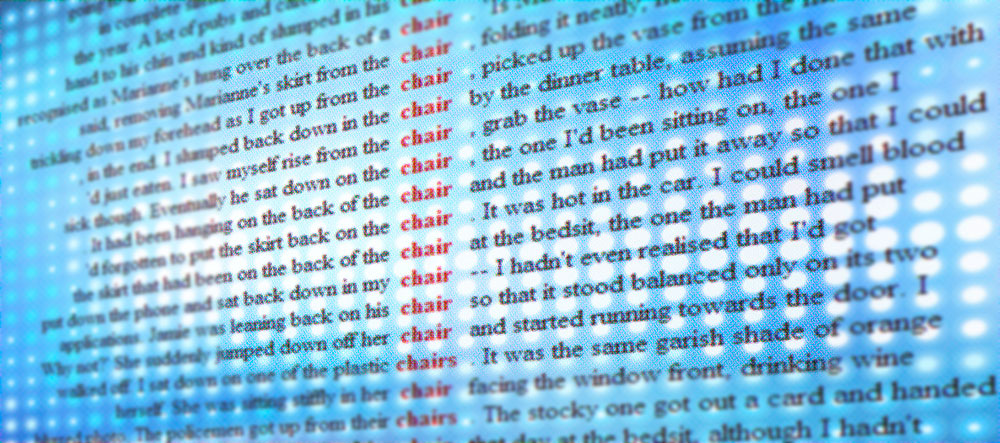

Compiling on screen using a purpose-built text editor required the acquisition of a whole new set of skills, since I had only ever worked on paper; but what really blew my mind was the corpus. Previously I had only seen concordances – the output of a corpus – on paper, since on my previous project we were able to request a printed sample of lines for particularly tricky entries. Engaging at close quarters with the corpus was a revelation. I was almost paralysed for several weeks, overwhelmed by the quantity and quality of the data I was expected to process. This corpus – soon to be rebranded as The Bank of English – was tiny by today’s standards, but the insights it provided into the behaviour of English were like nothing I had ever come across before.

Concordance lines for chair, generated by the corpus

At COBUILD we worked with the corpus differently from the way I have ever known it to be used anywhere else. Using specially developed software, we lexicographers (and grammarians) would analyse the evidence for the word we were compiling. We would then base our revisions of existing entries from the first edition, as well as all the new entries and senses we were adding, on that evidence. We were a large team and there was always a colleague available to discuss problematic entries or tricky decisions on how to divide up senses, but the evidence provided by the corpus was the basis of everything we did. I don’t think we ever looked at another learner’s dictionary. It sounds horribly arrogant, but we had no need to; we had all the material we needed right there in front of us.

I have worked on many corpus-based dictionaries and other projects since, and I rarely work on a dictionary that does not use corpus evidence to some degree. A corpus is always my first port of call when I encounter a new word or meaning. However, I think the COBUILD dictionary remains unique in being based so directly and completely on what only a corpus can give, which is evidence of how the language actually works.

This blogpost has been written by Liz Potter, who is a freelance lexicographer, editor and translator.