If you had never heard of a coronavirus before this year, you certainly will have now. As alarm increases about the spread of a new strain of this virus around the world, some people have been wondering about the significance of the word ‘corona’ in the name, even – if media reports are to be believed – to the extent of questioning whether there is any association between the virus and a popular brand of Mexican beer.

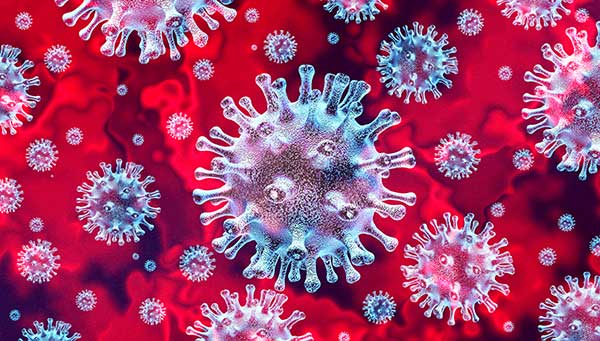

In fact, the name ‘coronavirus’ comes from the virus’s shape. When it is viewed under an electron microscope it looks like a sphere with spikes coming out of it. This caused the scientists who first looked at it to name it after the Latin word for a crown, which is ‘corona’.

Scientists often use Latin or Greek word-parts when they name things. This process creates long words that can be mystifying to the layman, but which can be decoded to reveal the essential characteristics of a thing.

Several other groups of viruses get their names from Latin or Greek words that describe their shape. These include the filoviruses (shaped like a thread), the rhabdoviruses (shaped like a rod), the rotaviruses (shaped like a wheel), and (rather pleasingly) the togaviruses, which are enveloped in a capsule thought to resemble a Roman toga.

However, there may be other reasons behind the names of virus groups. Some names reflect the part of the body that the viruses attack, such as the enteroviruses, which attack the intestines (‘enteron’ being the Greek word for the gut), and the rhinoviruses, which attack the nasal passage (‘rhis’ being the Greek word for the nose). Other names arise from the diseases that viruses produce: flaviviruses cause yellow fever and related diseases (‘flavus’ being the Latin word for ‘yellow’), while myxoviruses cause influenza and mumps (‘myxa’ being the Greek for ‘mucus’). There are also names that relate to the way that viruses behave or their mode of transmission.

These names are usually invented and agreed upon by the scientific community, and are rarely encountered by the wider population unless a major public-health alert brings them out of the scientific journals and into the mainstream media, causing us to reach for dictionaries or tap into search engines in order to find out just what it is that we should all be worried about.