“No man is an island, entire of itself.”

The truth of John Donne’s powerful aphorism has gone on receiving heart-warming confirmation – often in unexpected ways – during the current pandemic. For a start, in the UK the appeal for volunteers to help support the NHS in its darkest hour was massively oversubscribed. More than three times the number of people originally requested signed up, which demonstrates just how strong a hold the NHS has on the country’s hearts. Truly, “a friend in need is a friend indeed”, as the venerable proverb, which goes as far back as Euripides, has it.

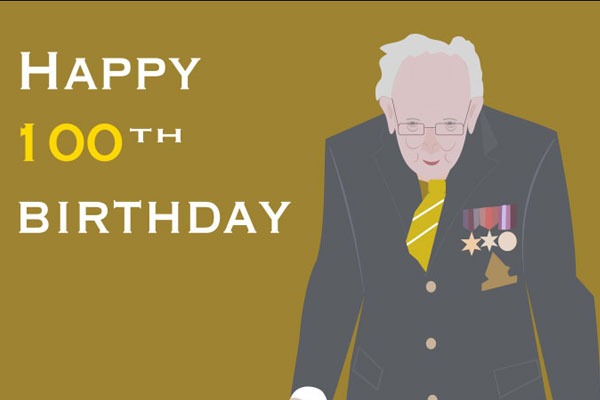

Mention of targets being exceeded, friends in need and the hearts of the nation leads us seamlessly on to the extraordinary story of centenarian hero Captain Tom Moore. This doughty Yorkshireman originally had the modest aim of raising £1,000 for NHS charities by yomping a hundred laps of his garden before his hundredth birthday, which falls today. That was to be his way of thanking the NHS for the treatment he’d received for cancer and a broken hip. As I write this, a day and a bit before that centenary, that target has been exceeded by a percentage that almost surpasses reality at 29,363 per cent. Not only that: the record he made with Michael Ball and the NHS Voices of Care reached number 1.

Happy Birthday, Captain Moore!

The NHS helpers were answering an official call to be part of an organized scheme. Captain Tom Moore’s appeal was, at least initially, a small, private initiative. But schemes that start out as small initiatives very soon mushroom fruitfully.

Take the Canadian caremongering movement. Since the middle of March, thousands of volunteers have joined what started out small, coming together to help their neighbours in multiple ways, in Facebook groups, on Twitter or in community hubs. The name was chosen, as one of the founders explained to the BBC, to be an explicit counterpoise to scaremongering. “Scaremongering is a big problem. We wanted to switch that around and get people to connect on a positive level.”

Back in the UK, the government mantra has moved on from social distancing to “Stay home, Protect the NHS, Save lives.” Only an enrolled member of the grammar police would suggest that, well, really, it should be “at home”. What the slogan loses in natural English it gains in oomph.

But once we start to come out of the current lockdown, social distancing will be top of the agenda again. This might seem like a stilted, cumbrous way to manage personal space. And I mean “personal space” in the very real psychological sense of the physical distance at which you feel comfortable talking with or being next to others. That distance varies from culture to culture, and some might argue that in Britain it has been whittled down to an “indecent propinquity”, to use an Edith Whartonian – she of The Age of Innocence – phrase. What with air-kissing – mwah-mwah – or, heaven forfend, even skin-contact kissing, traditional British reserve has been sorely tested and a much-too-close-for-comfort physical intimacy has been thrust even on older Britons. Whatever happened to that legendary stiff upper lip? Soul-baring and effusing are the order of the day. Perhaps the need for social distancing will re-establish a bit of old-fashioned decorum. Am I joking? Who can say?

Meanwhile, our social life is transformed. It is tempting to say “abolished,” given that pubs, restaurants and shops are shut. But no, social life carries on regardless, only now it’s virtual. And the national booze intake seems to be skyrocketing. We can’t go to the pub, but we can enjoy a virtual happy hour. There are virtual pub quizzes every night of the week. And the Zoom app has gone through the roof in popularity. But keeping in touch via Zoom can drain the brain, such that there is now talk of Zoom fatigue. Beware, too, of Zoom-bombing, that is, hackers and other miscreants gatecrashing your cosy confab or meeting.

So, we can still go on socializing virtually even if we are self-isolating physically. Isolate, incidentally, comes by a roundabout route from the Latin insula “island”. Which brings us neatly back to Donne.

By Jeremy Butterfield

Jeremy Butterfield is the former Editor-in-Chief of Collins Dictionaries, and editor of the fourth, revised edition of Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage.

All opinions expressed on this blog are those of the individual writers, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of Collins, or its parent company, HarperCollins.